Raised eyebrows…that’s what I got from people back when I said, “I live in Colón.” They weren’t exactly wrong to raise them. The province gets a bad rap because of its capital city, also named Colón. Steer clear.

But outside of that one permanently down-on-its-luck city is one of the most underappreciated rainforest districts in the Caribbean. Weekends, a local family by the name of Ehlers would adopt me. We’d pile into their Mitsubishi Montero, and go jouncing over potholes and plowing through mud to get to the heavenly coast of Portobelo. We weren’t exactly driving to the rainforest because it was all around us, deep green and so dense it was like a living, breathing organism, ready to swallow up the road and us with it.

Fishing boats—paint faded, lifejackets missing straps—ferried us from the settlement at La Guaira to Isla Grande, where a few “hotels” had simple cement boxes for rooms. We were happy to rough it. The rewards were great. We slept two steps from the island’s sandy edges, and the kiosk next door had cold 50-cent lagers. We’d sip and shuffle under the sun…soles of our feet getting hot on the beach and cooling down in turquoise waters.

Sometimes there’d be an event. A surf competition or carnival party. Then the locals who call themselves Congos—Afro- Panamanians descended from colonial-era slaves—would gather to show off a rich, centuries-old heritage of dance and song. Most nights there was nothing to do but talk and laugh. I learned to play dominoes, noisily slapping down tiles. Often the power would cut out at night. It didn’t really matter. We had candles.

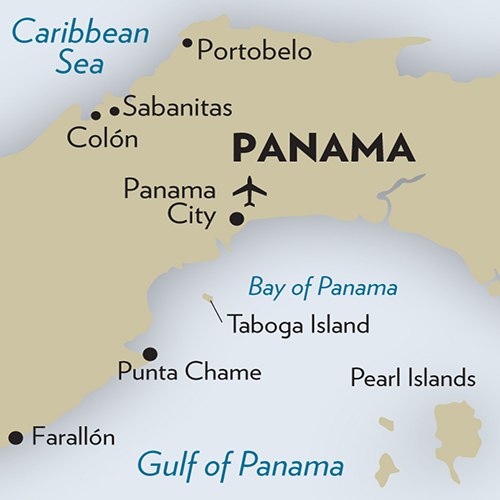

Now I’ve grown accustomed to a little comfort, and Portobelo has caught up. Things haven’t changed much on the surface. A significant portion of the district consists of national park that can’t be razed and developed. But you can stop at El Castillo for sushi with a Caribbean twist: garlic shrimp rolled in coconut rice. And hurrah, there’s free WiFi. And the drive is smooth and easy, with a new tollway from Panama City to Sabanitas. I go coast to coast, Pacific to Caribbean, in under two hours. It costs me $2.30 and two gallons of gas.

“Life is easier here now,” says New Orleans expat Rosalind Baitel, who splits her time between Portobelo and Panama City. “We know some areas are lacking. Internet can cost a bit more here than in the city, and speeds are up and down.” (And yet during the pandemic, Roz and I had several glitch-free virtual happy hours on Zoom.)

“But we have a great, close-knit community,” she says. “Everyone helps everyone. And this is not a retiree community. There are expats and locals of all ages here now.” Thanks to them there are better options for food and more places to stay, from boutique operations like Ciel y Miel to glamping at Tesoro Verde Panama.

Scots Heather Andrews and Jim Hood, both 61, are responsible for the jungle camp that is Tesoro Verde. They were slowly building their own home on 19 acres that may once have been a banana plantation. A friend saw the lush surroundings and unfinished home (no roof ) and said it would be perfect for glamping, or glamorous camping.

“Why not?” is something you hear a lot from people here. Adventurous, self-sufficient types that are always trying something new. And so in the spirit of why not, Heather and Jim started welcoming guests. You can sleep in a comfortable bed—not a cot, a hotel quality bed—under the stars. They also have a mud oven (they built it before they started on the house…priorities). On full moon pizza nights they light a few tiki torches and roll out pie after pie. Heather says you’re not allowed to leave till you can’t eat any more.

For me, people like Heather and Roz are what make Portobelo such a fun place to be these days (and here I must thank Roz Baitel for her extraordinary friendship, and passion for this region). I should also confess that Roz has a beautiful beach house in Portobelo, and invites me often. (Come live in Panama and make friends. Everyone knows someone with a beach house.)

Roz’s husband Allan is from the province of Colón and a director of Linton Bay, a new marina that’s already full of sailboats, yachts, and catamarans. Roz and Allan are also the community outreach liaison and co-founder, respectively, of Panasea, the first open-ocean sea cucumber hatchery in the Americas. Sea cucumbers are vital to the coastal ecosystem, so in addition to generating incomes and jobs, the project is helping the environment.

I went to tour the facility and had to smile. There were people in comfy board shorts and t-shirts, some of them busily walking about, others sitting in the open-air cafeteria fronting the water. I’d been expecting a bunch of serious boffins. These were relaxed, happy scientists.

David Grossman, co-founder and CEO of Panasea, has simple lodgings onsite, along with his staff. He and wife Ashly Tellez Grossman split their time between Portobelo and Panama City, where their daughter goes to school. “We do lots of swimming and snorkeling and make sandcastles,” he says. “There are always a few kids running around, doing kid stuff. It’s kind of a summer camp vibe. We also go to some off-the-beaten-path beaches nearby, like Playa Paraiso, a spectacular, super secluded beach. This is a great place for us and the kids.” A good thing, as the Grossmans are expecting twins any day now.

I’m not sure I ever want to sample a sea cucumber, but seeing outfits like Panasea set up shop here is exciting. They donate locally, lobby for better services, and many of them want to help preserve and restore the marine environment.

Playa Paraiso is a spectacular, secluded beach.

There’s Reef 2 Reef, a coral restoration project and Open Blue, an open-ocean cobia fish farm. (I recently tried the cobia sashimi-style. Delicious.) But I’m giving the prize for “project most likely to make your jaw drop” to Ocean Builders. They’re building apartment-sized seapods in Linton Bay, and the ribs of these futuristic structures are actually 3D-printed.

Unlike boats that move with the water, the seapods will be fixed in place so you can have 360-degree ocean views. Sounds like something for the rich and famous, but prices at time of writing are around $195,000. Like houseboats, the pods will be subject to annual flag fees. In total, they estimate maintenance costs and expenses will be around $500 a month. Yes, I just added “live in a seapod” to my bucket list.

Of course, there are already a lot of people living on the water in Portobelo. As many as 150 vessels (around 350 people) were steered to shelter in this region during the pandemic, the majority at the Linton Bay marina. I saw the marina in its early days, and today it’s hard to believe my eyes. It’s full of life. And so convenient. Each berth comes with water hook up and electricity and WiFi is available across the site.

I walk around with Roz one particularly hot morning. Monkey Island sits across from the marina, a tiny self-contained jungle. Even on cloudy days, the views are spectacular…but today the sun is shining bright, illuminating the water, making the colors pop. It’s a quintessential Caribbean day. A day to drink in the countless blues and greens that make this one of the most desirable regions on Earth.

We stop to say hello to Efraín, one of Portobelo’s most popular vegetable sellers. Back in the 1990s, fresh produce for sale in this region was very basic: tomatoes and onions, cucumber and carrots. Today Efraín will get you whatever you want from Panama City. Asparagus, strawberries, be as fancy as you like.

Alana Husby and Tony Urrutia, best friends who’ve rented a houseboat for a few months, are thrilled with the food selection. “When we moved out here, we brought all the food we could from Panama City. But then we learned about the veggie van. Beautiful tomatoes, basil, radishes…it was like a treasure chest,” says Tony.

“When he found fresh dill I thought he was going to have a heart attack,” laughs Alana. “One day we got three pineapples for a dollar, the most gorgeous pineapples you have ever seen. We can get fresh shrimp, the best garlic bread we’ve ever had, another supplier delivers wine to us on the houseboat…we’re doing very well here.”

When not in the mood to cook, they can grab lunch at a local restaurant. There are two in the marina. The Blue House is a fonda—a rustic, open-air eatery. It sits in a green field, where kids run around and play while parents sip a cerveza or café con leche. Every table and chair is different. Wood, plastic, it doesn’t matter, find a seat and order a heaping plate for about $7. Nancy serves pulpo and patacones (octopus and fried green plantains), rice and beans, hearty soups, thick-cut fried yucca and more.

Closer to the slips is Tropic Bar and Restaurant, known to many as Ray’s, after the friendly guy who runs it. It’s on the ground level of a pale blue double-decker building with wraparound decks. There are hats hanging in random places and handwritten signs on the columns. It’s got a hodgepodge look that says come as you are, and welcome. There are tables and chairs, food and drink. What more could anyone want?

Stop by and ask about the $7 burger of the day, it might be smoked pork and cheddar or something called the “hangover burg.” If there’s anything you need to know, this is the place to find out. Need a barber to come out to your house? Ray or a friendly sailor will look up from her brew to tell you what’s what. Not in the mood for company? You can send a WhatsApp message and get a fried fish sandwich delivered to your boat.

We got three pineapples for a dollar.

Life here could get expensive, especially if you’re eating out a lot. And living on a boat is a whole nother kettle of fish. “Running your boat is a full-time job,” says Alex, 55. He and wife Carla Sazunic Dorsey, 45, live on a 42-foot Westsail—an oldschool sailing boat, as Alex likes to say. “It’s not all sitting under palm trees, sipping umbrella drinks.” Yes, there are days like that… but there are also days spent covered in grease, fixing things.

In his blog, Projectbluesphere.com, Alex explains how to be a minimalist sailor. “We live 100% off-grid, on solar power, and we don’t burn fossil fuels much,” he says. “We make as much as we can… bread, pasta, tofu, cheese, wine…and buy as little packaged food as possible. We pay $185 a year for a cruising permit, and we’re not overpoliced. In the States they were always coming onboard, it could be really hard sometimes. Here, it’s more relaxed.”

Heather and Jim spend around $2,000 a month on a life she says is neither spartan nor profligate. The couple actually came to Portobelo on a small sailing boat, but in 2005 they decided to buy land. “It was dirt cheap, mainly because it was untitled. I wouldn’t recommend anyone else go that route, unless they were very well off,” Heather adds. It’s a common concern in this region—there is still a lot of “Right of Possession” property. It’s better to stick to land that’s already been titled, unless you can afford to gamble on land that might have multiple ownership claims.

Living on land in Portobelo can be extremely inexpensive for anyone happy to rent, though. But online, don’t expect to find much of anything besides expensive vacation rentals. To make the most out of life in Portobelo, you need to be willing to come down and talk to people. Take some time to greet them properly before asking questions. I’ve traveled extensively in the Caribbean and, from the Bahamas to Barbados, this is a good rule of thumb.

Some Spanish is necessary. But in my experience people in Portobelo are over the moon if you just show you’re willing to try. Polite holas and a bit of broken Spanish get you smiles and friendship.

For 30-something single expats like Jason Ashcroft and Amy Bennett, it was easy to network with locals and expats. And they each found creative ways to save on housing. A photographer and naturalist who offers jungle wildlife tours, Jason was offered free lodging at a little hotel if he would keep an eye on it at night. Later he and his girlfriend—they met in Portobelo— moved to a large property with a house for sale. He takes care of maintenance in exchange for discounts on rent.

“It’s a bit of a hike, but I like to be in the jungle. My neighbors are monkeys, sloths, and toucans. The house has three bedrooms, two bathrooms, a loft, and a nice terrace. It looks out over the forest, and I can see the ocean and enjoy the sunset. We have local fruit planted all over the property, so whenever we’re bored we go see what’s ripe. We compete with the monkeys for mango and avocado,” he jokes. “But the way I see it, it’s all theirs anyway.

Many places rent for about $500 a month here.

“I’ve seen many places rent for about $500 a month here. You might find waterfront to be more expensive,” Jason says. But if you have your own vehicle, you can access cheaper properties that aren’t right in town or along the main road. “I’d say anybody could survive out here with $1,000 a month.”

Amy came to Portobelo on a work exchange program and refused to leave when it was over. She started spay and neuter clinics for local animals, eventually setting up her dedicated charity, Stray Jim’s. One day, someone brought in a cat and got to chatting with Amy. He (the human) was returning to France and needed someone to manage his vacation rental property. Maybe Amy would be interested? “It fit both of our needs,” says Amy. “I was able to create my own income and have somewhere beautiful to live. Win-win!”

“I don’t think you can surpass Portobelo for the mix of jungle, beach, mountains, and culture,” Amy says. She is especially fascinated by the area’s history. The ruins at Portobelo are among Panama’s best-known heritage sites, the cannons still pointing out to the water: pirates beware. Across from El Castillo is another warning: Drake Island. They say the privateer, Sir Francis Drake, was buried at sea from here in 1596.

In the village center is my favorite local landmark, the Iglesia de San Felipe, a simple white church with pasty purple trim. Here lives the Cristo Negro, the Black Christ of Portobelo. His festival takes place on October 21. Every year brings a flood of pilgrims in satiny purple robes. They come to pray and give thanks for blessings. You’ll hear this one say, “I walked for two days.” And the other, “I traveled the last mile on my knees.” No one knows where the statue came from. There are several legends, and some say it’s over 350 years old.

If you’d asked me about Portobelo five years ago, I would’ve started with a list of caveats. Now, a long list of positive, exciting developments come to mind first. I can actually see myself living here again. Over the past year alone I’ve met expats of all ages and walks of life here. Single women like me, and single guys, too. I’ve talked to people who are straight, gay, white, Black… people in their 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s, and just hitting 70, too. And it’s a very international crowd. Yet they all have something in common. They’re independent, easygoing types. You’d have to be. This region has its challenges.

You may be dismayed by the litter and trash heaps that persist in some parts. Or be put off by the necessity of keeping reserve tanks stocked with rainwater. “But things have been improving,” says Jason. “When the power goes, it doesn’t stay off for a couple days. We get it fixed in a couple hours, even if it’s still storming.” There’s internet and cell service, and with the new Panama-Colón highway, Panama City’s hospitals are two hours away.

Portobelo’s outlook is positive, thanks in large part to the expats and locals who are investing their time and money here, and who want to make it better. Property and business owners like Rosalind and Allan, who are aware of and working on the issues. In the past year they’ve lobbied for better water and trash handling and created a chamber of commerce for the region.

Today I find myself falling in love with Portobelo all over again. And not just because I’ve spent so many happy hours lolling by the pool and jumping off the dock at Villa Rosalinda. I love that Portobelo’s effulgent Congo culture is getting more attention. Its “ritual and festive expressions” were recently recognized by UNESCO. And there’s more funding for exhibits and projects to preserve ancestral customs and knowledge. The costumes and dances, how to make the bongo-like tambores…all of it.

To this day, when I drive through the tiny Portobelo town center during carnival, a devil with gaping jaws blocks my way, demanding payment. “Un cuara.” (A quarter; the Congo lingua franca is a mix of Spanish, English, and French.) The ladies in the square wear bright patchwork dresses that show off their shoulders. One is obviously the queen, she’s wearing the largest crown you’ve ever seen. Another has no crown, but she flaunts poppy pink lips and tempts with a tray of tropical fruit.

¿Qu’e lo que tu trae’ pa’ vende’? a man sings, asking what she has to sell.

Hay papaya pa’ vende’ she trills, smiling her poppy pink smile.

More than anything, this is Portobelo. And if you want to look beneath the surface, and get to know it; the land, the people…the rewards will be sweet.

Jessica Ramesch lives in Panama City and travels Panama’s beaches, islands, and mountains in her role as IL Panama Editor. Panama@legacy.internationalliving.com.

Jessica Ramesch lives in Panama City and travels Panama’s beaches, islands, and mountains in her role as IL Panama Editor. Panama@legacy.internationalliving.com.

CLICK HERE FOR YOUR BONUS CONTENT

Editor’s note: In Panama, you can have it all—great weather, gorgeous beaches, fresh mountain air, warm, friendly people and all the luxuries you deserve…but at a fraction of the cost you’d pay at home. Dig into Escape to Panama: Everything You Need to Know to Retire Better, Invest Well, and Enjoy the Good Life for Less and get the inside scoop straight from experts and expats living there full-time. Learn more here.